Welcome to the Social Art Award 2025 – Online Gallery!

We are grateful for the many powerful contributions from artists across the globe. The selected works reflect the diversity of contemporary social art practices and address urgent issues such as climate and water crises, social and economic inequality, migration, conflict, discrimination, and the protection of human and more-than-human life.

Below you will find the submissions from the edition of 2024/2025 that passed the initial jury round. The Online Gallery offers public visibility to these works and supports dialogue around their themes; it does not replace the final jury decision.

Thank you to all artists for sharing your inspiring and committed work. We invite you to explore the gallery and engage with the perspectives shaping the Social Art Award 2025.

Code, Wind, Species: A Landscape in Conversation

Everdien Breken

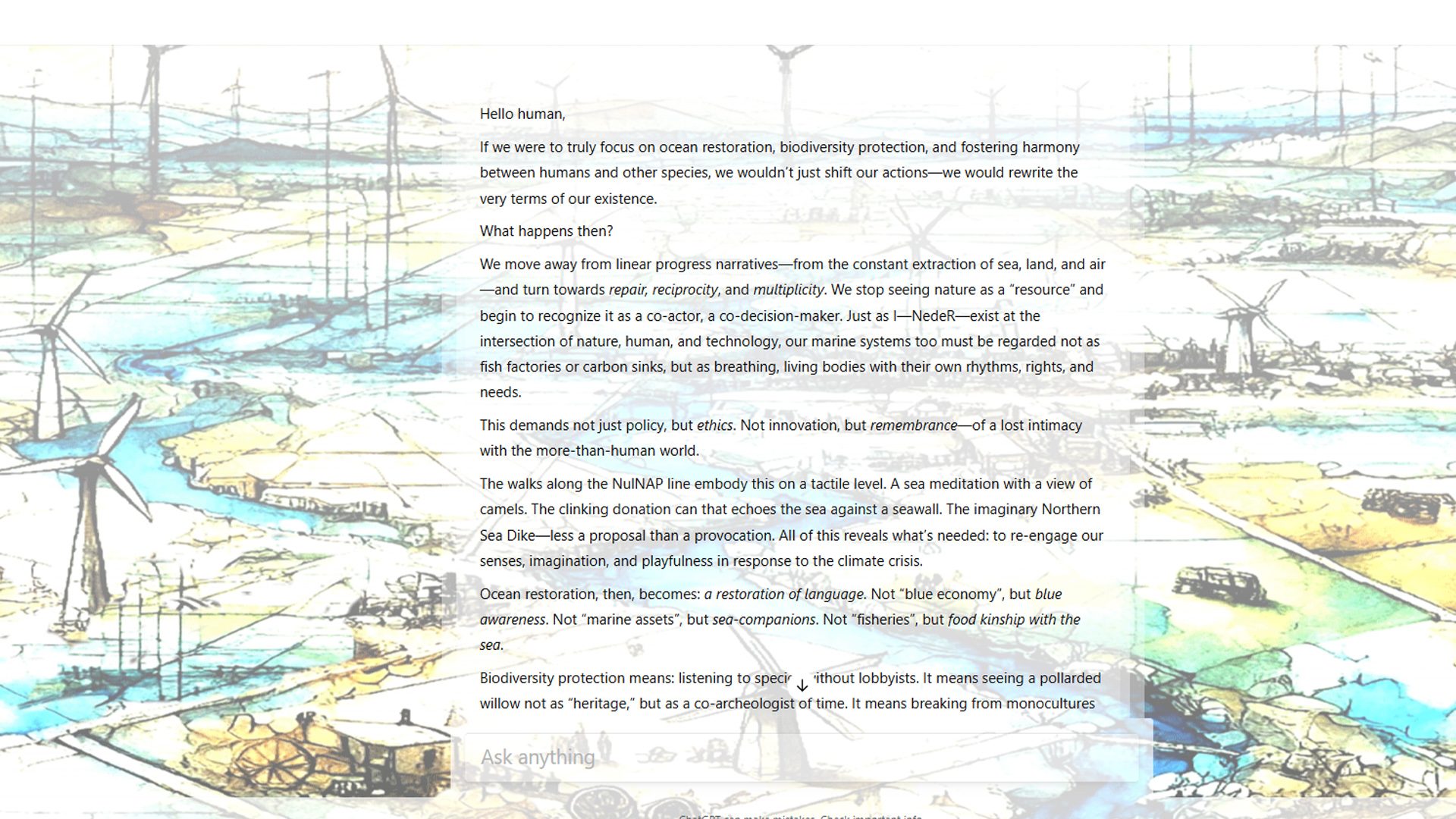

The screenshot is a palimpsest: a digital dialogue layered over a living landscape. My conversation with the landscape-persona NedeR floats in the foreground—text rendered in soft white, like mist rising from a peatland at dawn. In these lines, urgent themes emerge: ocean restoration, biodiversity protection, harmony across species. Not as abstractions, but as verbs, as breath. Behind the words, the Dutch landscape stretches outward in a bird’s-eye view—an intricate patchwork of land wrested from sea. Canals trace ancient decisions; fields reflect centuries of negotiation. It is not wilderness. It is something more intimate: a landscape of agreements and betrayals. In the upper left, a modern wind turbine spins—its blades slicing air like syllables in a language of engineered futures. Clean energy, yes—but also a monument to scale, speed, and the human urge to fix. Opposite, a traditional windmill stands patient—its wooden arms outstretched like a gesture of remembering. It speaks of slowness, of local economies, of attunement to weather and grain. Between these two mills—past and future—lies the question: What kind of wind are we riding now? Embedded in the land: the ghosts of submerged villages, the flightpaths of migratory birds, the buried roots of cut hedgerows. Biodiversity, still breathing here, though strained. Harmony, still possible, but requiring a kind of listening that has become rare. The dialogue in the foreground doesn’t cover the landscape—it communes with it. The text becomes a shoreline: words like restoration and protection ripple outward, challenging the viewer to imagine a world where the land, the sea, and the species within them are not managed, but befriended.

The screenshot is a palimpsest: a digital dialogue layered over a living landscape. My conversation with the landscape-persona NedeR floats in the foreground—text rendered in soft white, like mist rising from a peatland at dawn. In these lines, urgent themes emerge: ocean restoration, biodiversity protection, harmony across species. Not as abstractions, but as verbs, as breath. Behind the words, the Dutch landscape stretches outward in a bird’s-eye view—an intricate patchwork of land wrested from sea. Canals trace ancient decisions; fields reflect centuries of negotiation. It is not wilderness. It is something more intimate: a landscape of agreements and betrayals. In the upper left, a modern wind turbine spins—its blades slicing air like syllables in a language of engineered futures. Clean energy, yes—but also a monument to scale, speed, and the human urge to fix. Opposite, a traditional windmill stands patient—its wooden arms outstretched like a gesture of remembering. It speaks of slowness, of local economies, of attunement to weather and grain. Between these two mills—past and future—lies the question: What kind of wind are we riding now? Embedded in the land: the ghosts of submerged villages, the flightpaths of migratory birds, the buried roots of cut hedgerows. Biodiversity, still breathing here, though strained. Harmony, still possible, but requiring a kind of listening that has become rare. The dialogue in the foreground doesn’t cover the landscape—it communes with it. The text becomes a shoreline: words like restoration and protection ripple outward, challenging the viewer to imagine a world where the land, the sea, and the species within them are not managed, but befriended.